One thing that is important to keep in mind is that Ryan always approaches health care reform from a budgetary perspective. There's usually very little consideration paid to details like public health and the economic consequences thereof. That's not necessarily a bad thing since there are many aspects to the issue that need attention, but this method of problem solving has a tendency to cause a new problem for every old one that gets "solved." For example, what happens to economic productivity when tens of thousands of old people are forced to move back in with their children to be cared for in their twilight years because the bulk of their fixed income is devoted to treating a pre-existing condition that no private insurer will cover? That's an important question, but one Ryan never really anticipates during his thought experiments.

As we've noted in the past, Ryan knows a good buzzword or catch phrase when he sees one. In the Hoover speech Ryan promotes a concept he calls "patient-centered health care reform" without ever really defining what that exactly means. To be sure, he elaborates on the concept, but never really fleshes it out satisfactorily. This is no small matter since it appears to be the goal his plan aspires to reach.

Regardless, Ryan seems to think that this goal is within reach. The speech is divided into three segments. In the first, Ryan provides us with his assessment of the current political conditions that will make his reform possible. In the second, he provides the details of his plan for reform. Ryan uses the final part as a sort of pep talk to his audience. Obviously, it's the second part that's the most interesting and the one we're going to focus on.

The principles of Ryan's plan seem to be conveniently summed up in two words: choice and competition. In the speech's preamble he summarizes his proposed reforms by saying:

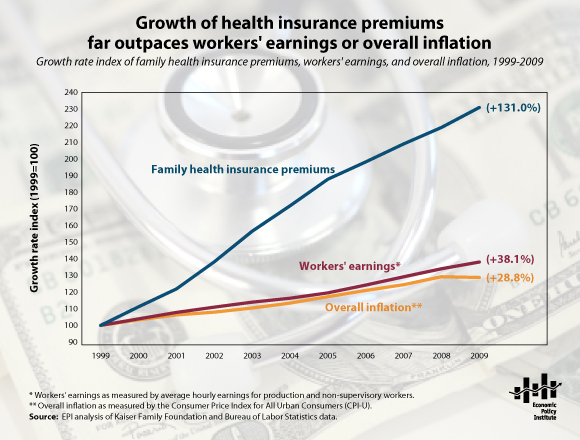

Thanks to the tireless work of health-policy scholars here at Hoover and elsewhere, we know what works and what doesn’t. Simply put, badly designed government policies are to blame for much of what is wrong with health care today, and the solution is clear: We need to transition from the open-ended, defined-benefit approach of the past… to market-oriented, defined-contribution reforms that promote choice and competition.Ryan's assumption that Government lies at the core of rising medical costs is dubious. Health care costs have exploded since 2000 and now far outpace inflation or wages:

If Government was the problem, they would have begun exploded shortly after Uncle Sam got into the insurance business in the 1960s, but that's not exactly what happened. Medical costs kept pace with the consumer price index until about 1980 then only really began to diverge in the early 1990s:

So what Ryan is essentially say is that it took doctors about 25 years before they finally figured out how to gouge Uncle Sam. Something tells me that with all those advanced degrees it wouldn't have taken so long. Neverthless, Ryan attributes this disparity to Medicare:

In Medicare, the government reimburses all providers of care according to a one-size-fits-all formula, even if the quality of the care they provide is poor and the cost is high. This top-down delivery system exacerbates waste, because none of the primary stakeholders has a strong incentive to deliver the best-quality care for the lowest cost.

Using Ryan's reasoning, private health care insurance should remain stable, or even decline, since there is no government interference and all three stake-holders are directly involved in the decision-making that goes into a patient's care, but even private insurance premiums have sky-rocketed:

This shouldn't be happening in Ryan's world. But it is. Was there some kind of law passed in the late 1990s that granted the government massive intrusive powers into the health care industry. Nope. (But there is an argument to be made attributing the ongoing increase in costs during the early 2000s to the Medicare Part D bill, which Ryan voted for.)

The conundrum posed by the cost of health is that while it is not only a problem, but also one of the great human success stories of the 20th century. Medicine currently is capable of doing things that were unimaginable just decade ago and while that's great for our overall quality of life, it doesn't come cheap. The expensive role of technology in modern medicine is a huge factor in escalating costs. Along the same line are the research and development costs that eventually get built into the cost of a treatment. For uncommon ailments, these costs can be considerable. And that's not a small issue because sick people are living longer thanks to some very expensive treatments. These are good development, but expensive ones.

Medicare is certainly going to be a burdensome expense, but it's just a small part of the problem compared to the projected costs of all health care costs in the near future:

So Ryan's diagnosis ignores the fundamental causes that result in more expensive care. It should be surprising that his proposed solutions do the same.

The solution in each of these areas is to move away from defined-benefit models and toward defined-contribution systems. Under a reformed approach, the government would make a defined contribution to the health-care security of every American, rather than continue to offer open-ended, well-intentioned, but ultimately empty promises.This is another way of saying vouchers. This has been discussed elsewhere at great length.There are inherent problems with a voucher plan that replaced Medicare with partially subsidized private insurance plans. The most obvious is the likely unwillingness of private insurers to take on elderly customers, many of whom will likely have previously diagnosed conditions.

The growth of these defined contributions should be capped, to reduce the inefficiencies that have led health-care costs to spiral out of control. But they should be adjustable so that more help goes to the poor and the sick, while less financial support goes to those who are fortunate enough to need it the least.

That sounds nice, but all Ryan's plan does is move a pile of money from one hand to another without addressing the inherent costs that make health care so expensive.

Ryan then goes on to contradict himself when discussing the high cost of private insurance, which he blames on taxes:

[O]ur current tax code provides additional fuel for runway health care inflation. Under current law, employer-sponsored health insurance plans are entirely exempt from taxation, regardless of how much an individual contributes to their policy.

This tilts the compensation scale toward benefits, which are tax-free, and away from higher wages, which are taxable. It also provides ways for high-income earners to artificially reduce their tax-able income by purchasing high-cost health coverage – which in turn can fuel the overuse of health services.

So overuse of health services isn't just a problem that results from Medicare, but happens with private insurance as well. Blaming this phenomenon on taxes strains credulity. It's the supply-sider equivalent of the equant.

The most frustrating thing about this brief detour into reality is that Ryan actually touches on the fundamental problem with health care today: the incentive structure for health care providers is out of whack. Health care providers have every reason to run expensive, unnecessary tests when they charge by the x-ray and not the complete treatment. That would put the onus on the private sector to change, though -- a concept abhorrent to Ryan's Randian worldview.

The problem with just about anything Paul Ryan policy is that it evolves from an Utopian ideology and not a critical look at the circumstances as they actually exist. Ryan frequently peppers his speech with the phrase "cost-effective," but if this was actually a goal it would be nearly impossible to not look at other countries that provide comparable universal health care at a significantly reduced cost. Ryan wants a world in which the free market actually works efficiently and rationally and maybe even morally ... and if that world doesn't exist, he'll just have to create it.

Part of the Ryan mystique has resulted from a confusion between substantive ideas and effective marketing. Ryan never misses a chance to supply his plans with web sites, YouTube videos, cable interviews or roll-outs at think tanks and that's a large part of the reason why he enjoys such a highfalutin reputation among his colleagues. The Hoover speech is remarkably free of data and heavy on ideology -- that's never a good sign -- and it wouldn't be the first time Ryan has tried to mold a world to his own specifications.

Unlike Ryan's health care reform, which is still very theoretical and will likely never leave Conference Room C of the Hoover Institute, there is a more radical (by American standards, at any rate), though much less publicized, plan that will actually begin covering patients:

Vermont governor Peter Shumlin [has] signed into law a plan meant to transform the private-run health insurance industry into a the nation's first government-funded, government-run health care system that offers a uniform benefit package to every eligible resident. The first phase of the law will extend coverage to all 620,000 Vermonters through the option to participate in the state health benefits exchange called Green Mountain Care, which Reuters reports, "will set reimbursement rates for health care providers and streamline administration into a single, unified system." Per a federal mandate (read: Obamacare) the exchange will offer coverage from private insurers as well as state-sponsored and multi-state plans. The plan also calls for tax credits to make coverage affordable for low-income residents.This is actually happening. Slowly, but it's happening. The American health care system is becoming far too expensive to be feasible for much longer and countries that have public health care coverage are far more adept at reigning in costs:

As we mentioned earlier Ryan devotes a lot of his speech to surveying the political landscape and discovering that it's a good foundation on which to build. Not once does he mention Vermont. In five or ten years time Vermont will begin to feel the effects of its experiment. If the results are positive, other states will might follow suit (think Minnesota or Oregon). Ryan's plan is all or nothing, which is usually how plans described as being "bold" work, and the closer you look at it the easier it is to see that there's not much there to begin with.

No comments:

Post a Comment